Where are the Women?: A Star Wars Story

Warning for Rogue One spoilers.

For how much we commended Lucasfilm on its great strides towards gender diversity since The Force Awakens, I think a lot of us forgot to look more closely at Rogue One until it was already out. Not everyone—god knows I been pointing out the severe lack of women since last year alongside some friends—but enough. After Phasma, Rey, Maz and Leia, and the diverse background characters in The Force Awakens, perhaps it was too easy to become complacent. Too easy to believe that once we’d taken that step forward, it was impossible to fall behind again.

Well, apparently fuckin’ not, because Rogue One barely even tries, if I’m completely honest. The tough-white-brunette-as-lead doesn’t really make up for a distinctive lack of other women anymore—not that it ever should have. As much as Rogue One seemed to want to cling to some Star Wars traditions, the sole-white-female-heroine-among-men is one that should have been thrown right out with the opening crawl (though I remain forever broken-hearted at the lack of the crawl).

Especially when the ancillary material is working more than it ever has to create a diverse galaxy, introducing women like Admiral Rae Sloane, Doctor Aphra, Cienna Ree, Shara Bey, Brand, Sabine Wren, and even more amazing women who veer away from the typical Star Wars films’ leading lady. I would give anything to see any of these women, or women like them, on the big screen, and it’s disappointing to watch Rogue One fail when so many other stories within the universe succeed. Especially because I know Star Wars can do better. Especially because I love Rogue One as much as I do.

Experience, Empathy, and Robin

The first time I saw Robin as a work in progress, I was struck almost speechless. A cute little indie game is right up my alley, and a cute little indie game about Chronic Fatigue Syndrome is basically everything I’ve ever wanted. Even better: it’s made by a group of kiwi students who are the sweetest.

Robin’s main mechanic is based off of the Spoon Theory, a common way for chronically ill people to explain their limited energy reserves: as you make Robin perform actions, her energy bar empties until the only option is sleep. It’s simple but effective, and evocative of daily life for someone with Chronic Fatigue. A rapidly depleting energy bar is a part of life for us, not just a game mechanic.

However, though chronically ill people may find their lives reflected in some form in Robin, I suppose we must ask the question: can a game ever actually help able people empathize with those who are chronically ill? Can a game really make someone understand in a way that positively changes their thought patterns?

Yeah, probably.

Being Something: Asexuality in BoJack Horseman

BoJack Horseman is a weird show. It treads a fine line between dark humour, satire, depression, and, though not ever-present, hope. It’s ridiculous, and, at the same time, totally and inexplicably human. That a show starring an anthropomorphic horse-man could so deftly capture human struggles could say a lot of things, but perhaps the distancing from the real world is what helps the show swerve so quickly from inane to heartfelt.

So it shouldn’t have been any surprise that BoJack would be one of the first shows to introduce one of its lead characters as asexual—though still unlabelled, and perhaps not ace, but something very close. In hindsight, it’s no surprise that BoJack would do it; at the time, however, it was jaw-dropping. Not just because of the fact it happened, but because of how it was treated.

Leia Organa, and the Women Left Behind

Spoiler warnings for Version Control, Unwind, and The Fold.

Let’s talk about ladies. More specifically, let’s talk about god damn General Leia Organa, biological daughter of the biggest mistake of the galaxy and the bravest queen to ever grace Naboo’s picturesque vistas, adopted daughter of verified owner of the Galaxy’s Best Dad mug. At the tender age of nineteen, she stands up to Vader himself; decades later, she’s leading the only resistance the New Republic has against the First Order.

She is vitally important, not just in the GFFA, but in science fiction in general. Why? Because she still has her voice. She falls in love, becomes a slave (ugh), gets married, has a kid — and years later, she still has a voice.

How Civil War Revives Ultron’s Black Widow

Since her introduction in Iron Man 2, Natasha Romanoff—better-known by her superhero alias, Black Widow—has, until very recently, had to fill the role of Sole Female Superhero in the Marvel Cinematic Universe’s Avengers franchise. From her absence in toy lines, to the way her various directors have bounced her between the rest of the Avengers for the sake of sexual and romantic tension, to Marvel not giving her a solo flick, it’s pretty clear that being Black Widow isn’t always all it’s cut out to be.

Despite all of this, Natasha Romanoff has managed to grow from unknown-to-casual-film-goers into an almost universal fan-favourite. She is one of the metaphorically strongest heroes in the MCU, no doubt a reaction to Marvel not giving her a solo movie. Or rather, she’s a strong and compelling character when it’s a film directed by the Russo brothers.

Otherwise? Ehh.

Start With What You Know Is True: Mental Health in The Hunger Games

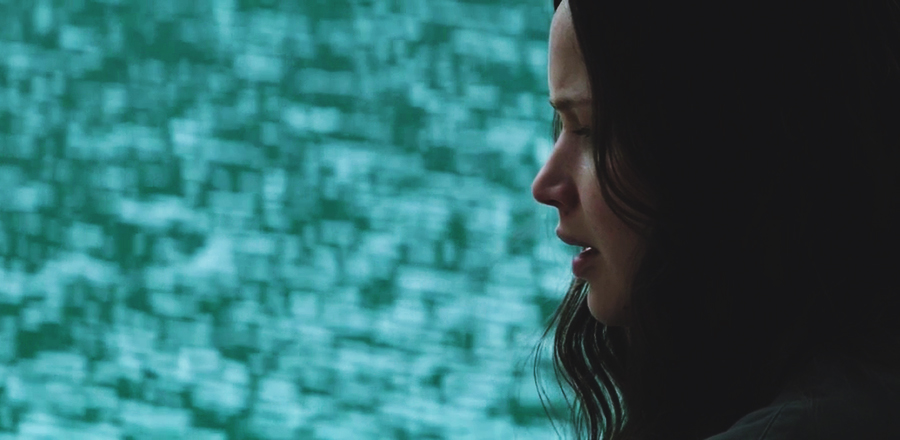

In the real world, mental illnesses affect millions of people, and yet there’s often a silence surrounding the issues, brought on by social stigmas and a lack of education on mental health. Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and anxiety and panic disorders are prevalent within The Hunger Games, experienced by Katniss Everdeen and those around her. The trilogy highlights just how much trauma can affect people, especially the young adults and children manipulated by those much older.

While the novels are far more adept at portraying the characters’ understanding of and struggles with their respective illnesses, the films do make an effort. The opening scene of Catching Fire, where Katniss hallucinates another tribute from the Games while hunting with Gale, visually captures the nightmares of the arena that plague Katniss, setting up the audience’s understanding of her mental state following the 74th Hunger Games. The majority of Katniss’ interior struggles, however, are found within the pages of the books.

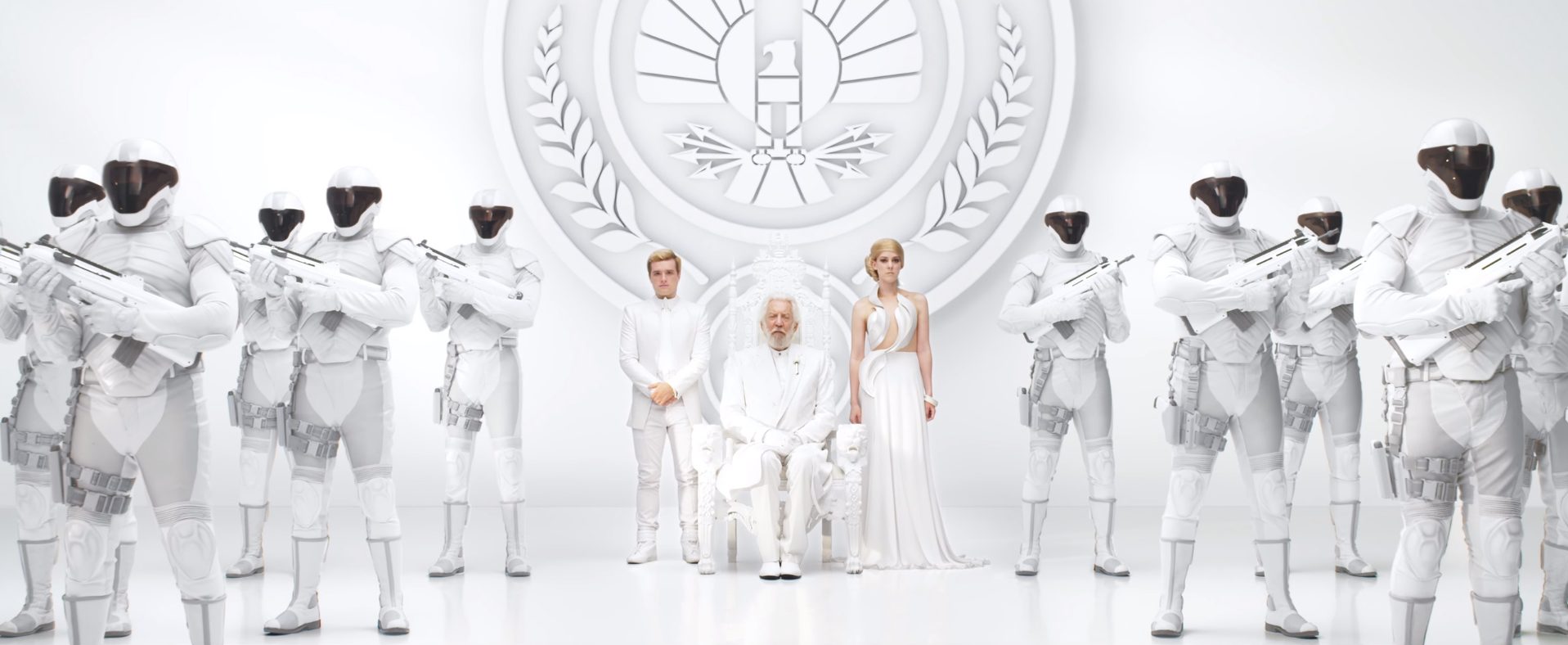

Panem Today, Panem Tomorrow, Panem Forever in Our World

Katniss raises her bow and lets loose an arrow, blowing a Capitol hovercraft out of the air. As it crashes into a second craft and they plummet to ground, the screen bursts into flames, and then: the Mockingjay logo over black. We watch this in the theater at the end of a trailer, Panem sees this at the end of a rebel propaganda short—a propo. The Hunger Games reflects a darker version of our own future, but our world reflects Panem right back.

Young Adult dystopian fiction is not a rare genre to find. Divergent, The Chemical Garden, Delirium, Uglies, Unwind, Chaos Walking, the list goes on. There are a vast array of reasons young adults connect with dystopian fiction. Give them a world they can see coming in their own future, a land destroyed by those before them, rules that tear away their agency, adults who would manipulate them, and yet give them the strength to grow, to change the narrative of their world for the better.

By wiping away the tedious normalcy of our lives now and exaggerating the things that already make life harder for everyone such as surveillance, media bias, body autonomy, and more, YA dystopian literature manages to not only distill issues in our present, but warn of future problems.

Of Bows and Sabers, and the Girls who Wield them

2015 was a year of great cinema, that’s without a doubt, but the best part? That the two most anticipated of last year—The Force Awakens and Mockingjay Part 2—had something in common other than their sci-fi foundations, something that is still unfortunately new in action and science fiction and big blockbuster films: female leads. Rey, and Katniss Everdeen. Not adults, but girls, both thrown into their respective stories while still teenagers.

Though similar in their survivalist personalities and ability to defend themselves, having learned their fighting abilities simply to survive their harsh lives, both Katniss and Rey have vastly different personalities. Maybe it’s the traits that parallel the two that make them work so well as leads, and their differences that create such compelling young women as they fight for their lives, and the lives of those close to them.

Female Protagonists, Who Cares?

While at PAX Australia earlier this month I tagged along to a panel called, Who Cares About Female Protagonists? with a friend because, well, I care about female protagonists a hell of a lot.

There’s a reason the majority of my favourite games are headed by women and girls, or at least give the player the option to pick their gender (props to you, BioWare.) These games make me feel like I can be a hero in a way male-led games do not. They make me feel like I can be something more than I am.

To See Ourselves in Fiction

I’ve always been that person who constantly and consistently fights for other people–be it for better or worse–but has never worried too much about herself. When it came to representation in media, I’ve always been vocally backing up that yes, we need trans people, we need people of colour, we need asexuals and aromantics and all the other facets of the LGBT+ umbrella.

But I never really worried about myself, I never felt I needed to see people I identified with in the shows, books, games and movies I love. Sure, I was bitter at the utter refusal from shows like Orange is the New Black to use the b-word (bisexual, the word is bisexual), but I reiterate that actually seeing a bi gal on the silver screen didn’t feel vital to me. Other people needed (and still do need) that representation more.

And then The Legend of Korra happened.